Meet a Blind Oceanographer

Meet Amy Bower, an oceanographer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

Dr. Bower has been curious about the world ever since she was young, and she now studies the ocean by going on sea expeditions and analyzing the data she gathers as a blind scientist. In 2007, Dr. Bower founded OceanInsight, an outreach program for blind and visually impaired learners of all ages. Read on to learn more about Dr. Bower and her work.

What made you want to become a scientist and learn more about the ocean?

As a kid growing up in a small coastal community in Massachusetts, I developed a really strong curiosity about how Earth works, particularly the weather and the oceans. I spent hours as a kid turning over rocks in tide pools to see what lived underneath. I'd watch the tide come in and wonder why that happened. Like many kids in snowy regions, I was also a dedicated weather-watcher, always with my ear to the forecast in case a big snowstorm might mean "Yipee! No school!" Watching and listening to these forecasts made me wonder why sometimes we got rain and sometimes snow, and why some storms were windier than others. I also grew up at a time when there was growing interest in environmental conservation, so that influenced me a lot; I wanted to help understand how the natural environment functions so we could all do a better job preserving it.

What is it like to work on a boat as a blind person?

One might think that a boat is a dangerous place for a blind person-especially a working research ship with equipment all over the place in an unfamiliar setting. But it's not as bad as one might think. First of all, it's a pretty small space, so it's easy to figure out how to get everywhere I need to go in just a couple of days: the ship's lab, my cabin, the galley (where we eat), and the bridge (where the ship's crew and scientists manage all the activities going on). Just like I do when I travel anywhere new, I take extra time to make sure I know how to escape from my cabin or the lab in an emergency. I go through all the escape routes until they are memorized. Because the ship can move a lot in the waves, there is a big emphasis on keeping all the equipment tied securely in place, so all the walkways are clear and safe for everyone. There are some data displays on the ship that are visual-only, and therefore not accessible to me, so I need to consult with an access assistant-someone whose job it is to make sure I have access to all the same information as everyone else on board.

What tools do you use in your research, and how do they help you study the ocean? How do you collect and study data?

I use several types of equipment that measure ocean currents. I release freely drifting buoys that sink way below the sea surface to track the pathways of deep ocean currents. These drifters are tracked underwater using sound. I also use special sensors that are anchored in one place and measure the speed and direction of the ocean currents flowing by, as well as the temperature and salt content of those currents.

I was normally sighted until my early 20s. Since then, I've lost most of my useful vision slowly over time. When I still had some vision, I used video magnifiers a lot to read and look at data graphs. I used screen magnification on the computer for the same tasks. As I lost more vision, I depended more on screen readers, which I use extensively now every day. With a computer screen reader, I can read and write reports, read and write emails, have Zoom meetings with other researchers, write computer software, etc. Graphics are more challenging and I use several approaches for accessing them: swell paper (raised line or tactile) drawings, data sonification, 3D printing, and (most often) sighted assistance.

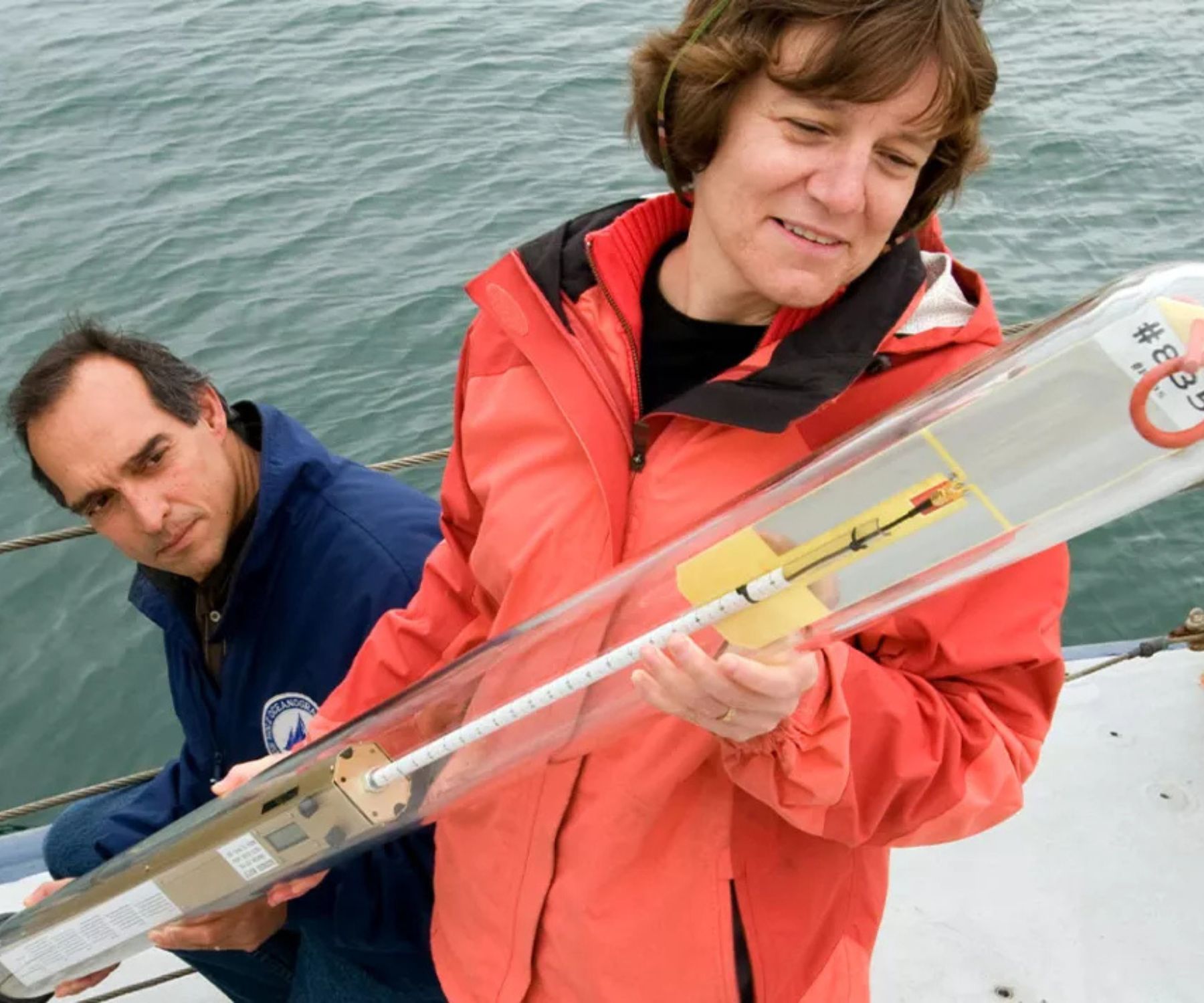

Amy Bower and operations leader David Fisichella display an instrument for measuring the depth and temperature of the ocean.

Photo: Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

What were some of the challenges you experienced when you lost your sight and how did you overcome them?

The biggest challenge has been to learn how to do science without sight. Maybe that is obvious, but for most of my educational years, I was normally sighted and learned how to be a scientist using my vision. Starting in my 20s, I had to start learning a whole new way of being a scientist. It hasn't been easy, but I've managed to continue my career as a scientist by taking one day at a time-that is, keeping my focus on the challenge right in front of me and not worrying too much about what might happen later, when my vision further deteriorated. Another way that I managed to stay on track in my career was to find others with similar challenges and get to know them and how they solved their vision-related problems. It was very helpful to realize that I was not alone in facing the challenge of first low, then no vision as a scientist. When I was at the beginning of my career, it was hard to find other scientists who were blind, but over the years, more and more blind and low-vision individuals have decided to pursue a science career. As this community has grown, there has been more incentive to find ways to make science more accessible for all.

What is the most surprising or unexpected thing you have learned in your research?

Using drifting buoys that trace out the pathways of ocean current far below the surface, my colleagues and I have discovered that the currents in the deep sea are far more complex than initially thought. For example, in the past, oceanographers thought there was only one deep current flowing southward in the North Atlantic, carrying cold Arctic waters away from Greenland toward the equator. Now we know there are multiple pathways. These deep currents are part of a global system of flows called the Great Ocean Conveyer, which is very important in regulating Earth's climate and taking excess atmospheric carbon dioxide produced from burning fossil fuels into the deep ocean, where it will remain for hundreds of years.

What tips do you have for blind kids who are interested in pursuing a career in science?

If you are interested in science, don't let blindness or low vision cause you to think you can't become a scientist. New technology is coming along to make science more and more accessible every day. For example, image description with AI is quickly becoming a tool I use for description of some scientific images and graphics. Also, there is more and more recognition by employers that people with disabilities, including those who are blind or have low vision, have tons to contribute to science, technology, engineering, and math. Another tip is to develop excellent blindness skills, including orientation and mobility, and computer skills (including screen reader use). Practice advocating for accommodations even in your school-that is an important skill. You are entitled to accommodations by law, but you will need to let others know what you need for accommodations. It can sometimes be hard at first. Starting with some easier requests can get the ball rolling, and eventually you will feel more comfortable requesting other accommodations.

What advice would you give to a blind or visually impaired person going on a boat for the first time?

Ask a sighted person to give you a very thorough orientation to the boat or ship, identifying special hazards. Make sure you are extremely familiar with all the safety protocols, including escape routes. Ask someone to be a "safety buddy"-this is someone who will make sure you are safe in an emergency. If you are prone to motion sickness, bring some medication, and try to keep yourself busy and occupied.

Science students from the Perkins School for the Blind visited the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution for a day of field work hosted by Dr. Amy Bower.

Photo: Cape Cod Times/Steve Heaslip